What drives Great Britain’s electricity generation mix?

As my colleague Tom Jones, noted in his blog on electricity prices, the electricity generation mix in Great Britain (GB) is going through significant changes. This blog looks at the generation mix in more detail and how it's changed over time.

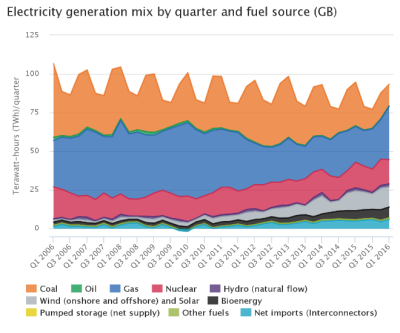

Over the last ten years or so, the amount of electricity produced from carbon intensive energy sources (mainly coal and oil) has declined sharply, while output from renewable sources has increased more than fourfold over the same period.

The graph below demonstrates this shift in the generation mix over time. In the first quarter of 2016, coal and oil’s share in the total generation mix was just over 15%. In comparison, jointly coal and oil accounted for almost 47% of the total generation mix in the first quarter of 2006. Renewables’ share of the mix was just over 4% at that time.

Source: Ofgem Data Portal - Wholesale Energy Market Indicators

The latest data shows that gas-fired power stations continue to generate the largest share of electricity in GB accounting for almost 37%, up from around 28% a decade ago (although gas’ share has fluctuated between 27% and 47% over the decade). Renewables (mainly wind and solar) make up almost a quarter of the total, and nuclear, 17%.

This shift towards a higher renewables share has taken place both through policies to encourage the construction of new renewable generation capacity and an increase in costs faced by carbon intensive generation. The introduction of the Carbon Price Floor (CPF) and the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) has increased the costs for coal-fired power stations, reducing their profitability. Lower power prices and a fall in power demand have also played an important role by reducing income from these plants. And, as a result, a number of coal plants have closed.

A fall in the day ahead contract price of gas since April 2013 has been one of the key drivers of low GB power prices in recent years (David Hall discusses what affects GB gas prices in his blog) with power prices now at their lowest level since the financial crisis began in the late 2000s. Low power prices have in turn influenced the speed at which this change in the total electricity generation mix has occurred.

Low power prices have made coal plants less profitable to run, whilst cheaper alternative generation capacity has grown in recent years. For these reasons over a number of days this May, there were short periods during which coal didn’t contribute to the UK’s electricity mix for the first time since the first coal power station began operating in 1882. Looking ahead, coal’s share in the total generation mix is set to fall even further as a lot of the older generating capacity is expected to retire in the coming years. In November 2015, the government announced that all coal-fired power stations would close by 2025 as a part of the commitment to bring down UK carbon emissions.

In contrast to falling profitability of coal-fired power stations, economics of gas-fired power stations has improved. Even if gas-fired power stations can’t compete with renewables on running costs, they are well-placed to fill a short-term shortfall in intermittent renewables’ output. Electricity from gas tends to be a lot less carbon intensive than coal and consequently it isn’t as affected by CPF and ETS charges. Low gas prices have also contributed to the rise in the importance of gas in the generation mix.

What does all this mean for the future of power generation in GB? Renewables will remain an important part of the overall generation mix as capacity grows, helped by decreasing costs. And, given its flexibility and relatively low cost, gas is likely to continue to play a key role in responding to variations in solar and wind power output. But, also new forms of flexibility such as electricity storage and voluntary demand-side response may make a greater contribution towards balancing the system in the future. Meanwhile, similar to coal, the majority of existing nuclear generating capacity is ageing and due to come offline in the next decade. Over this period, both nuclear and coal will continue to provide a steady but a decreasing share of the total power supply.